Zoe Liu wanted to study pipelines, but someone beat her to it.

She pivoted. Instead of studying natural gas flows between countries, she focused on financial flows. This brought her back to her home country of China, which invests the largest stock of foreign currencies in the world.

Who manages the money? What are their goals ? Will the Chinese system become a model for other countries? She answers these questions in her new book: Sovereign funds: how the Chinese Communist Party finances its global ambitions.

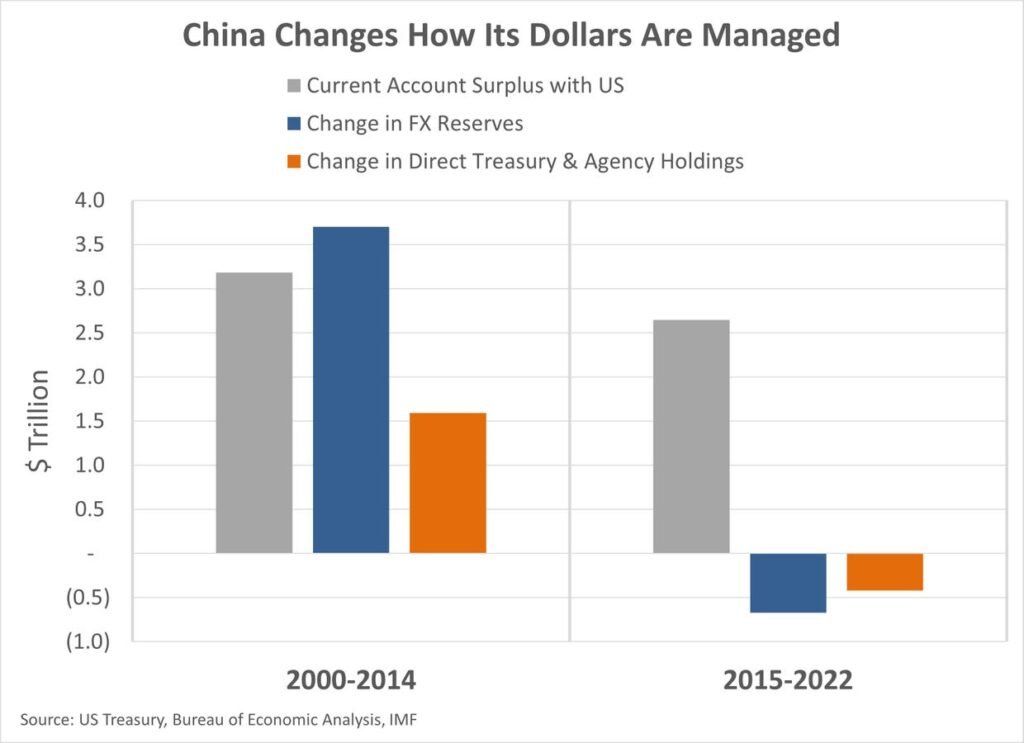

The chart below shows the big picture. China runs a huge current account surplus with the United States. Before 2014, it stored this income as reserves, investing much of it in U.S. Treasury and agency bonds.

China no longer adds its dollar income to foreign exchange reserves.

Then things changed.

The second set of bars shows what happened. The surplus with the United States still exists, but the accumulated dollars are no longer added to the reserves. Instead, the money is transferred through a network of what Liu calls “leveraged sovereign wealth funds.”

What are these funds and how do they invest?

Central Huijin: China’s “chief shareholder”

When China transitioned to capitalism, its state banks were mere “cashiers” that funneled money to politically privileged borrowers. The results were predictable. By 2001, about 20% of these loans had become uncollectible.

Central Huijin was created to solve this problem.

It began in 2003 as a special policy instrument and was allocated $45 billion in foreign exchange reserves as capital. This money was used to plug holes in the balance sheets of state banks. Once balance sheets were restored, some of the largest banks sold their shares to foreign investors and were subsequently listed on the stock market through IPOs. This is a surprisingly successful way of leveraging foreign exchange reserves to solve an important domestic problem.

A few years later, Central Huijin successfully carried out a restructuring of the brokerage industry, and over time it became the “chief shareholder” of Chinese financial institutions. Its stakes in banks, brokerage houses and insurance companies give the state immense capacity to influence financial markets. Liu believes Central Huijin could currently help calm the storm sweeping the asset management industry.

China Investment Corporation (CIC): the global investment partner

By mid-2006, China’s foreign exchange reserves reached $900 billion and 70% was invested in U.S. Treasury or agency bonds. The central bank (PBOC) deemed the strategy appropriate, but the Ministry of Finance (MOF) deemed investments in low-yielding U.S. government bonds to be too large. In 2007, the MOF took over and the CIC was established under its jurisdiction to invest in higher yielding assets.

Things started off badly.

CIC’s first purchases were direct stakes in several US financial institutions whose value fell during the GFC. Although the CIC eventually recouped its losses, national publicity was poor. To diversify its financial risk and adopt a more discreet profile, CIC turned to indirect investment via foreign private equity funds.

This contributed to domestic publicity, but quickly attracted regulatory scrutiny and negative press in foreign countries. CIC has changed its position again. It began allocating money to “partnership funds” – joint ventures with politically connected companies in local countries. The CIC has partnership funds in many countries, notably in the United States, Germany, France, Italy and… Russia.

It was clever. For example, CIC partners with Goldman Sachs in the United States. In 2019, the partnership fund agreed to buy Boyd Corp, an engineered materials manufacturer. Congress initially blocked the deal, but Goldman managed to get the decision changed. Two years later, despite dire relations between the two countries, the fund was allowed to invest in Project44, a Chicago-based supply chain technology company. It’s impossible to imagine CIC completing these deals without Goldman’s help.

CIC’s learning curve wasn’t just financial. Over time, its investments shifted from being primarily focused on returns to acquiring assets deemed strategic by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). These include foreign resource companies and domestic technology companies. It also supports the CCP’s agenda by providing loans to state-owned enterprises as they “exit” and acquire stakes in companies operating in priority sectors. Perhaps as a reward, the CIC gained more power at the expense of the PBOC by bringing Central Huijin under its umbrella.

Not so sure: National Foreign Exchange Administration

The PBOC did not accept this loss of power without reacting. Starting in 2011, its foreign exchange management arm, SAFE, began moving money into a network of foreign and domestic investment funds that could control $1.3 trillion. The actual amount is difficult to know because only a portion of SAFE’s funds are listed in PBOC reports.

Like its rival CIC, funds controlled by SAFE are increasingly focused on politically important areas. The most important is the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Xi Jinping’s vision of linking countries to China through infrastructure projects. One of SAFE’s funds, Buttonwood Investments, capitalized the Silk Road Fund, the BRI’s main financing vehicle. SAFE has also been a pioneer in providing foreign exchange loans to state-owned enterprises at below-market rates. This helps them acquire stakes in foreign companies operating in politically important sectors.

Is your head spinning? Mine was too, so I tried to simplify it all into a summary table:

Chinese sovereign wealth funds cooperate and compete globally.

A book that can no longer be written

Could Liu write her book if she started now instead of eight years ago? I asked this question during our interview on Ideas laboratory podcast.

His answer: probably not.

Chinese sources are said to be reluctant to talk and she may be breaking “foreign espionage” rules. This is a shame, because there is much to admire about the way China has professionalized and adapted the way it manages its wealth.

A more transparent approach would generate less skepticism and concern in other countries, which would work in China’s favor. Unfortunately, there is unlikely to be more transparency, so we’re lucky someone else is writing about pipelines so Zoe Liu can continue her research on Chinese sovereign wealth funds.